DNA: Law enforcement benefit; privacy issues

- Kevin Elliott

- Oct 22, 2019

- 18 min read

Once mostly thought about in the realm of criminal investigations, the use of DNA technology has since expanded into the area of entertainment, as websites like Ancestry.com and 23andme.com make it possible for anyone with $100 to submit a swab of DNA from their cheek and trace their ancestry. But the vast amount of information contained in the genetic code sent to commercial databases is increasingly being accessed by law enforcement, raising privacy concerns.

Perhaps even more alarming is the number of possible uses of DNA information in the future, as data people once believed was private is sought by public and private entities.

"There are some privacy issues, and it should cast a light on what you're giving to these direct-to-consumer (genetic testing databases)," said Donald Shelton, a retired Washtenaw County Circuit Court Judge now serving as director of Criminology and Criminal Justice Program at the University of Michigan in Dearborn. "They have everything. There's a big difference between a fingerprint and DNA. It contains your medical history and everything."

First developed for use in the medical field, DNA can now be used to trace genealogy, produce a physical description of an unknown person and predict the probability of illness and disease. Used properly, the information can be used to track down lost relatives, produce new leads in unsolved crimes, or prove a person's innocence who has been wrongfully convicted. However, left with unrestrained access, the same information could be used in the future to deny medical insurance coverage to individuals with a genetic predisposition for certain diseases or drag an innocent person into a criminal investigation.

"This uncanny ability to identify specific individuals based on an exam of DNA makeup is a double-edged sword," said retired Judge Donald Shelton. "It has a tremendous ability to identify and incriminate individuals, but has equal power to exonerate individuals. We know it's an astronomical likelihood that a DNA sample at a crime scene came from a suspect, but it also has the same certainty that semen or blood didn't come from that suspect. We now have over 2,000 people that have been exonerated by the use of DNA. Between 25 and 40 percent of those who were wrongfully convicted were convicted by using other forms of forensic evidence."

Considered an infallible silver bullet for crime scene investigations, DNA evidence can provide a certain link connecting a person to a specific location. But while the science is exact, it is still prone to some human errors.

"DNA doesn't mean the person committed a crime," Shelton said. "If semen, for instance, is proof there was penetration, it can also tell you that a person did or didn't leave that evidence. A rape case that has DNA evidence only means that a person was there – they didn't necessarily commit the crime. You have to be careful when saying that DNA proves identity. It proves who left it, but not that they did or didn't commit the crime."

In some instances, it's actually possible for investigators and jurors to rely entirely too much on DNA evidence. Take for instance the case of James Chad-Lewis Clay, who was convicted in 2017 of raping a teen in Detroit 20 years prior.

Despite claims of his innocence, investigators found Clay's DNA inside the victim, which led to his conviction. The conviction was later overturned when Detroit Free Press reporter Elisha Anderson showed the victim a photo of Clay from his teenage years – at which point she recognized him as someone she dated and with whom she had consensual sex. Clay was subsequently released from prison. DNA in the case had gone untested for nearly a dozen years after being held by police.

The case is one example of why DNA evidence doesn't – or shouldn't – always result in a conviction, or in rare cases, results in a wrongful conviction.

Robyn Frankel, who heads the Michigan Attorney General's Conviction Integrity Unit and serves on the state's Wrongful Imprisonment Compensation Act board, said the Clay case is the perfect example of why DNA must be considered in context.

"You need to remember DNA is an incredibly powerful tool, but it's not unlike other evidence. You have to look at it with all the other evidence of the case," Frankel said. "Clay went to prison because it was a DNA match. It's the quintessential case that says 'just because your DNA matched doesn't mean you committed a crime.'"

Still, Frankel said DNA is crucial to bolstering convictions and in excluding suspects or proving innocence. When looking at wrongful imprisonment compensation cases, she said many cases involve convictions made prior to the widespread use of DNA testing.

"When looking at those that have been vacated, many are connected to DNA," she said. "Everyone knows about the 11,000 untested rape kits found in Wayne County, and some of those have now been able to identify suspects and exclude others."

In 2009, the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office discovered more than 11,000 rape kits that had been untested for years in an abandoned evidence warehouse. In August, Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy said all of the kits have been tested, leading to the closure of more than 3,000 cases and earning 197 convictions.

Greg Hampikian, a forensic DNA expert and professor at Boise State University and a founder of the Idaho Innocence Project, also said DNA evidence alone isn't enough for a conviction. Rather, he said, there are other factors that still have to be investigated.

"There are many facts and parts of a story that are part of a conviction. You have to look at each of those facts to find a conclusion," he said. "One of the challenges is that as instrumentation has gotten so sensitive, improvements in evidence collection by first responders and police officers hasn't improved that much. We are detecting single cells, and if there's an old bit of DNA somewhere – DNA is pretty stable – it may not mean anything even though it's part of a crime scene investigation. In some cases, you have one sperm cell, which has a very small amount of DNA, and there are other people who have had contact with the victim or live in the same house. You have to be careful about inference of small amounts of DNA that may transfer from another person. There has to be more caution."

In some cases, the information about DNA may influence findings of lab technicians.

In 2010, Hampikian and his colleague Itiel Dror, a cognitive neuroscientist with the University College London, conducted a study that looked into potential complications of DNA evidence. The study sent evidence from a 2002 Georgia rape trial that had relied on DNA to 17 different lab technicians. Results were mixed, with some labs finding the evidence inconclusive and others excluding the defendant as a suspect. Just one found the defendant was a positive match.

"It's well established that humans are subject to subjectivity," Hampikian said. "We are still waiting to see if that man will be free after 20 years. In the case, the original analyst had access to information of what happened, and because of that it may have been influenced. It corroborated what the co-conspirator was saying. But we showed the evidence to 17 other labs, and only one included the defendant."

Hampikian said such issues can arise when the lab technicians are familiar with the investigators and cases in which they are testing evidence.

"That's a very fertile ground for bias," he said. "If there are disputes or gray areas, like a mixture interpretation, then subjectivity and bias become more important because many people you know have a particular desire for a particular result."

Hampikian said removing labs from police and making analysis available to the defense and the accused would help to ensure guilt or innocence in a more timely manner. As it is now, a prosecutor can order a test, and it will happen, he said, while a defense attorney has a much harder time.

"It's not that analysts are doing sloppy work, but humans like me and other analysts will come to conclusions when they shouldn't. That's what the national survey shows," Hampikian said.

A survey, conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, centered around a hypothetical bank robbery that involved a ski mask recovered at the crime scene. The fabric of the mask showed a mixture of DNA from four people, which initially appeared as a mixture of two. Labs were given two of the four likely contributors, as well as a fifth that never had any contact with the mask. Sent to more than 100 labs, at least 70 percent got the answer wrong by including the fifth, innocent person, in the DNA mixture.

As Hampikian said, the results show that while DNA sensitivity has increased, interpretation of those clues hasn't always kept pace.

"The goal was to see how many labs would say (the mixture) is too complex to interpret, but the majority forced it and got the wrong interpretation, often including someone who was innocent," he said. "There's nothing wrong with asking a lab (to look for findings), but demanding an answer is probably a problem."

Hampikian said there is a more recent push to allow computers to make a determination of whether DNA is linked to specific persons in complex evidence mixtures. However, computer models are still programmed by humans, with potential to input bias into software.

"It's programmed by people and operated by people who can choose certain inputs and can use it beyond its capacity," he said. "There is a linear response with each of these instruments where they are reliable. If we push them – sometimes we are pushing things beyond their validated limits."

Despite the possibility of human error with DNA evidence, the use of it remains an invaluable tool for law enforcement, and is expected as evidence by the majority of juries hearing violent crime cases, particularly rape cases.

"Jurors will expect and perhaps demand DNA in rape cases," said Shelton, who studied jury expectations, surveying more than 1,000 random jurors in the Ann Arbor area in a former study. "But DNA only establishes penetration. In many cases, the issue is consent. So the expectation that DNA will handle all legal issues is misplaced."

Outside of the criminal justice world, the use of DNA has countless applications, from developing vaccines to making it easier to trace a family tree. However, as DNA technology advances, its exact uses, as well the access of your DNA information by others, is unknown. To better understand the capabilities and differences of DNA use, it is necessary to understand basic advancements in the field.

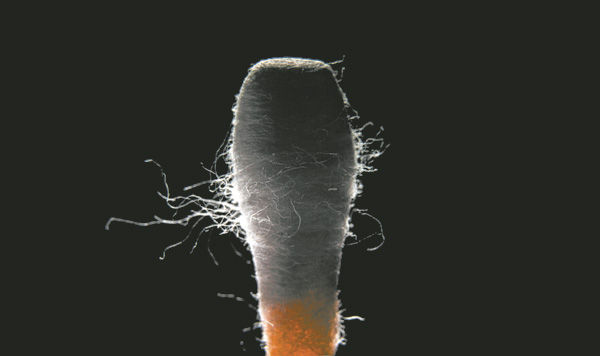

Historically, DNA use, particularly by law enforcement, has involved Short Tandem Repeat (STR) analysis, which compares specific locations on DNA from two or more samples. Essentially, the technology is used to compare a DNA sample, which could help law enforcement to either include or exclude a person as a suspect.

In 1990, the FBI started a DNA database program, which was later expanded into CODIS. The database includes DNA information on known offenders, those arrested for crimes, and information collected at a crime scene, which may not be linked to a specific known person. CODIS contains more than 13 million offender profiles, three million arrestee profiles and more than 840,000 forensic profiles.

"They started collecting DNA over the past 30 years, originally from those convicted of felonies, and now by Supreme Court approval, as part of the booking process, so this large database has developed," Shelton said. "But the database isn't lots of samples. The DNA is analyzed and a 'description' of the DNA is recorded, which is numbers and letters in the database.

The Michigan legislature updated the state's DNA collection and submission laws in 2015, following the Supreme Court's approval in 2013 of DNA collection at the time of a felony arrest. The Michigan State Police (MSP) CODIS Section receives and processes DNA samples, which are linked to an overall CODIS database that includes samples from throughout the country. Names and other personally identifiable information aren't stored in the database, but rather that information is retained by law enforcement agencies.

Under the state's DNA Identification Profiling Systems Act, individuals arrested for committing or attempting to commit any felony are required to provide a DNA sample to law enforcement.

The legislature updated the law two years later with a package of bills requiring the state police to dispose of an individual's DNA under certain circumstances. Those situations include: a written request from the investigating police agency or prosecutor indicating the sample is no longer necessary for investigation or prosecution; if the state police receive an order or request by a court certifying the complaint was dismissed or resulted in an acquittal.

The American Civil Liberties Union in 2015 was behind an effort to ensure DNA evidence would be removed from the database after a person is cleared of a crime.

The FBI states that DNA information in CODIS may be expunged when: a lab receives a certified copy of a final court order documenting the conviction has been overturned; or for arrestees, if the participating lab receives a certified copy of a final court order documenting the charge has been dismissed, resulting in an acquittal or no charges have been brought within the applicable time period.

"A lab will analyze evidence and put it into the national database, and if there is similar DNA in there, they will have a match. However, for many people and some crimes for sure, there is no match. Usually that means whoever left the DNA hasn't been entered into the system. In that case, we have a DNA sample, but don't know who it belongs to."

While the federal DNA database contains only a snapshot description of a person's DNA, databases maintained by commercial databases using direct-to-consumer testing contain raw samples of DNA. As such, samples are typically used to find certain genetic traits. However, the same sample can be used to develop much a greater range of information.

As others submit their DNA information, the databases can be used to find people who may be related to each other. Sites typically don't identify other users, but allow them to communicate and have the option of identifying themselves. Going further, GEDmatch was founded in 2010 to help amateur and professional researchers and genealogists, including adoptees searching for birth parents. GEDmatch allows users to upload their raw DNA data from the commercial companies and identify potential relatives who have also uploaded their profiles.

It was with GEDmatch that genealogy and crime investigation first intersected. In April of 2018, GEDmatch was used by law enforcement to identify a suspect in the Golden State Killer case, which involved a serial killer, rapist and burglar who committed at least 13 murders, 50 rapes and 100 burglaries in California from 1974 to 1986.

By accessing the commercial databases, law enforcement can expand their search for a DNA match. However, the same DNA may be used to find relatives of a potential suspect who may help locate that suspect. It can also be used to build a genetic profile of a person, which can predict hair color and type, estimated height, eye color and other information of an unknown person.

"Police can hire a genealogist who can build a family tree, and using their tools use public data to scour out relatives," Shelton said. "Who is the right age, height – all of that is in there."

In the Golden State Killer case, law enforcement had DNA evidence for years but never found someone to match in CODIS. It wasn't until investigators used DNA and GEDmatch to build a family tree and expand results. Investigators then obtained the suspect's DNA from a used soft drink container.

"Sure enough, it popped up that it was him," Shelton said. "He wasn't in CODIS because he was a cop."

Going even further, Virginia-based Parabon NanoLabs developed a snapshot DNA Phenotyping service, which creates composite face imaging sketches based on DNA samples using specially developed algorithms. The lab also is able to identify family members from commercial databases and determine kinship between DNA by six degrees of relatedness. The lab is one of the leading third-party service providers to law enforcement agencies, resulting in an average of one case solved per week, since May of 2018.

"They are all lead generation tools. They don't replace traditional forensics for identifying someone," said Parabon Vice President Paula Armentrout. "We can do that because of single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNP (snips). That is the blueprint for any human and the information rich part of the DNA ... in the early 2000s, we started analyzing DNA when trying to sequence the human genome.

"In 2009, we got federal funding from the Department of Homeland Security, and we started looking at SNPs. About the same time, 23andMe and Ancestry.com were taking off, and they used SNPs that required about 200 nanograms of DNA – that's a lot of DNA. Most crime scenes, you're lucky to get one nanogram. We turned genotyping on its head. We found you can do it with a lot less than 200 nanograms, so we set about changing the protocol. Everyone thought we were crazy."

Initial uses involved therapeutic utilization and clinical testing, but the advances led Parabon to work with the U.S. Department of Defense.

"That started the path to DNA phenotyping," Armentrout said. "Say someone left an unexploded IED on the road, and we could get DNA from it. That can tell you something about the person who planted it. We can mine the human genome and probably tell you the ancestry of a person, what they may look like, including skin pigmentation. We found we can get a pretty good likeness."

Kinship references were first thought of to identify POWs from wars who were previously unidentifiable. Parabon then offered the service to law enforcement, as mandated by its contracts.

Armentrout is quick to point out that the services offered to law enforcement aren't used as evidence for an arrest, rather they are for generating leads when other investigative avenues have been exhausted.

"They aren't making arrests based on names we give them. We give them names to investigate. It's up to them to go out and do the work," she said. "We can say this group is related or these are cousins, and should have the same genetic makeup as the perpetrator. It's up to them to get the match at the end using STR, or short tandem repeat analysis. That's the approved forensic process, and that's a fingerprint of your DNA. Lead generation is all we do."

Knowing what privacy protections may or may not exist may be an important factor for those considering submitting DNA strictly for ancestry purposes.

"Insurance companies want that information, and they might treat you differently for nefarious purposes," Shelton pointed out.

While current law prohibits access to such information for commercial reasons, Shelton said it is currently possible that DNA information is used without someone's knowledge to conduct broader research.

"It started with them saying, 'We will only release it to certain people, and not sell it' – but some of them do," he said. "They have been selling it for some period of time, but not the identifying information. But maybe at looking at the overall population to determine what percent will develop Alzheimer's, or something like that."

Christine Pai, a spokeswoman for 23andMe, said that the company stores user samples, but gives customers the option to destroy those samples if they choose, as well as the option to have their account deleted at any time.

"23andMe does not sell, share or lease any customer's information without their explicit consent," she said. "It is against 23andMe's privacy policies to share any information with employers, insurance companies, law enforcement agencies or any public databases, even if a customer is deceased."

Further, Pai said company policies prohibit it from voluntarily working with law enforcement, and "has never given customer information to law enforcement officials," and that it doesn't share customer data with any public databases or with entities that may increase the risk of law enforcement access.

Ancestry.com's privacy policy states that it will not share personal or genetic information with third parties without written consent. "In particular, we will not share your genetic information with insurance companies, employers or third-party marketers without your express consent," according to the policy. While Ancestry doesn't volunteer genetic information to law enforcement, it does provide advance notice to users if they are compelled to disclose information through the legal process.

GEDmatch uses an "opt-in" policy that allows users to determine whether they want to share information with law enforcement.

"They wanted people to opt in, and I have argued both sides of what is our ethical and moral responsibility," Shelton said. "If my DNA can assist with police in finding a rapist or murder, what is my ethical obligation? These aren't just the 50-year-old Golden State Killer, these are current cases.

"I've opted in. Frankly, if it was a relative or not, it doesn't make any difference. I choose to exercise my ethics by saying 'if this helps another victim, then I should do it."

Frankel, with the Michigan Attorney General's Office, wasn't so sure.

"What if I left my DNA somewhere where a crime happened to be committed," she questioned. "In general, you can't date DNA. It's the context that allows you to date it."

In terms of accessing private databases, the only state that prohibits familial searching of databases, or locating relatives of a suspect, is Maryland.

In September, the U.S. Department of Justice released its interim policy on forensic genetic genealogy, which combines DNA analysis with traditional genealogy. The policy, which goes into effect on November 1, 2019, gives criteria for when the use of forensic genetic genealogy can be used.

"When using new technologies like forensic genetic genealogy (FGG), the department is committed to developing practices that protect reasonable interests in privacy while allowing law enforcement to make effective use of FGG to help identify violent criminals, exonerate innocent suspects and ensure the fair and impartial administration of justice to all Americans," the policy states. "The interim policy establishes general principles for the use of FGG by department components during criminal investigations and in other circumstances that involved department resources, interests and equities."

Under the policy, suspects can't be arrested based solely on genetic association. "If a suspect is identified after a genetic association has occurred, STR DNA-typing must be performed, and the suspect's STR DNA must be directly compared to the forensic profile previously uploaded to CODIS," the policy states. "The comparison is necessary to confirm that the forensic sample could have originated from the suspect."

The policy also states that FGG work may be considered "when a case involves an unsolved violent crime and the candidate forensic sample is from a putative perpetrator, or when a case involves what is reasonably believed by investigators to be the remains of a suspected homicide victim. Additionally, the prosecutor may authorize the use of FGG for violent crimes or attempts to commit violent crimes other than homicide or sexual offenses when circumstances surrounding the criminal act present a substantial and ongoing threat to public safety or national security."

The policy goes on to state that before an investigative agency attempts FGG, the sample must first be uploaded to CODIS and have failed to produce a match.

"Agencies shall identify themselves as law enforcement to genetic genealogy services and enter and search profiles only in those services that provide explicit notice to their service users and the public that law enforcement may use their service sites to investigate crimes or identify human remains," according to the DOJ policy. "An investigative agency must seek informed consent from third parties before collecting reference samples that will be used for FGG, unless it concludes that case-specific circumstances provide unreasonable grounds to believe that this request would compromise the integrity of the investigation."

Despite not having the ability to use genetic genealogy investigations at its labs, the use of DNA by the Michigan State Police is exploding, said Jeff Nye, assistant division director of the department's forensic science division.

"There's definitely a huge expectation that DNA has been analyzed in cases," Nye said, noting a 41 percent increase in requests for DNA analysis from 2013 to 2018. "If you think back to 1996, when I started, we had five DNA examiners. Now we have well over 90."

While the state has added capability, the demand for DNA testing across the state means there still remains a backlog of samples to test.

"With every new technology comes a new set of potential applications of DNA," Nye said. "Sensitivity has increased, so we are able to get DNA profiles from smaller samples, so that opens the net for more sample types to be submitted, and that has outpaced our ability to hire new individuals. That said, we went into the new fiscal year and got 14 new DNA scientists, so that's a nice enhancement in our ranks when the state budget is focused on infrastructure and roads. That lends itself to the importance of forensic DNA."

Nye said there still needs to be additional education about DNA evidence, as is evident by what many call the "CSI effect."

"They understand the time it takes to get a result, but if there's an episode of CSI they watched, we have people trying to submit the same evidence when it's not good," he said. "We need a lot of education."

The Michigan State Police operates eight DNA laboratories in the state. Additionally, the Oakland County Sheriff's Office operates its own forensic lab capable of analyzing DNA and uploading information to CODIS.

"It's invaluable," Oakland County Sheriff Michael Bouchard said about DNA evidence. "In a lot of scenarios, it's a very unique identifier. When you have that at a crime scene, it's incredibly powerful and persuasive, and it's part of what we do with our lab."

Because the department operates its own forensics lab, Bouchard said investigators can utilize DNA evidence for non-violent crimes, such as burglary. Agencies relying on state-run forensic labs tend to focus DNA evidence solely on violent crimes.

"Say you have a serial burglar in a neighborhood and they cut themselves and leave DNA," he said. "If you can solve it, and they did 200 or 300 homes, that's invaluable."

Bouchard said while some agencies are utilizing expanded uses of DNA, such as genealogy searches and phenotyping, he said his office hasn't done so.

"We haven't attempted to expand the collection. We feel pretty good just collecting when people are arrested and convicted, or if you have a suspect with probable cause, we get a search warrant," he said. "Michigan law is pretty specific as to when you can collect."

Michigan law allows DNA to be collected at the time of booking for felony arrests or in cases where probable cause exists. There are no state laws in Michigan prohibiting police from working with third parties for additional DNA services.

As DNA technology continues to advance, the public might expect that everyone's DNA could – and will be – accessible, eventually.

"Anytime there's an investigation, there's a loss of privacy," Hampikian said. "Where does the balance favor loss of privacy or protection of the greater population? We have courts for that, and to get certain information, you can go to court. But other methods are legal. It's legal to pick up cigarette butt and test it, but to detain a person is illegal unless you have a warrant.

"It's a totally different world than what I grew up in. I'm now 57," he said. "Because so much of our lives are documented in one way or another, we can tell where someone was and what they post online, and it's changing dramatically in terms of DNA. The number of profiles that are or will become available soon are as large as the number of people that participate, even after they die. I think we will have a lot of DNA data pretty soon. Eventually, we won't have DNA we can't identify."